在1949年的7月,當蔣介石的國民政府軍隊與官員撤至台灣的時候,英國的《經濟學人》(The Economist)連續兩個禮拜,在16日與23日刊載了以台灣為主題的報導。

其中,7月16日的文章是在刊登在該週的「本週記事」(Notes of the Week)一欄,題目是〈福爾摩沙的未來〉(The Future of Formosa),全文如下:

福爾摩沙的未來

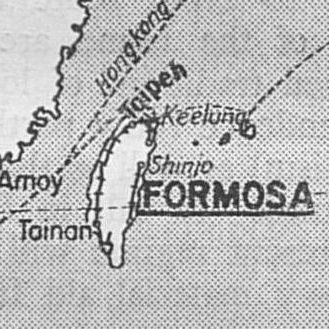

蔣將軍從他在福爾摩沙的堡壘前往菲律賓的旅程,使得福爾摩沙的前途問題比先起前更加緊張,該地直到與日本簽訂和平條約之前,在國際法下仍屬於受中國佔領的日本領土。目前該島被當成是來自中國北部與中部的國民黨官員與其家屬的避難所,也是國民政府從大陸帶來據說數量達300,000人部隊的堆置場,同時還是國民政府的海軍基地,用來封鎖上海與天津,以應付令人相當不安的共產黨以及嚴重受損的英國與美國貿易。目前蔣氏與其統治福爾摩沙的副手們,可以稱得上是廣州國民政府的後繼者,而且是根據初期協議,在日本和平條約締結前由中國佔領福爾摩沙。不過蔣氏政權在福爾摩沙很大程度上是獨立於任何外部權威,且若是共產黨取得廣州,將會帶來法律的瓦解與現實的不穩。這座由日本人在經濟上開發的島嶼,有著蓬勃的對外貿易,不過這可能無法維持太久,畢竟島上現在還堆放著士兵。共產黨並未有發動真正跨海入侵的立即可能,但如果國民黨無法再繼續支付並餵養其部隊(他們的家在大陸),兵變將會在不久後爆發。福爾摩沙人與日本投降後來自大陸的入侵者之間所存在的緊張關係,使得狀況更加複雜化。福爾摩沙人在1947年時發起反抗,但遭到非常嚴厲的鎮壓。這場叛亂並不屬於共產黨,而是屬於省份自治主義者,此外對任何程度上暫時獨立的強烈需求已知存在於福爾摩沙人之間。他們一直是中國國內一種難以控制的因素,且經過五十年與中國的分離,在一套壓迫而有效率的外來治理之下,他們毫無接受大陸「解放者」剝削的意願,無論解放者是國民黨或共產黨。

目前沒有人對福爾摩沙居民的期望給予關注,但相關的考量應該値得討論。若是以後撤銷對國民政府的承認,那麼與該政府之間所訂下關於福爾摩沙在戰後暫時性佔領的協議也將會廢止,除非這些協議能明確地在共產黨政府的認可之下更新;與之同時,最高權力會回歸到盟軍最高司令官,做為其對所有日本領土職責的一部份。如果美國人希望這樣,可以對聯合國組織委員會提供充足的保護,以讓福爾摩沙人在未來舉辦全民投票。不過目前沒有跡象顯示華盛頓有考慮在任何遠東政策中加入新事項。終究,若是對於福爾摩沙有任何疑慮,仍然可能會在預期中的國務院遠東白皮書中顯現。

The Future of Formosa

General Chiang's journey from his stronghold in Formosa to the Philippines has made more urgent than before the question of future of Formosa, which until a peace treaty is signed with Japan remains in international law Chinese-occupied Japanese territory. At present the island serves as a refuge for Kuomintang officials and their families from northern and central China, as a dumping-ground for Nationalist troops, said to number 300,000, brought there from the mainland, and as a base for the Nationalist naval blockade of Shanghai and Tientsin which is being operated to the considerable discomfort of the Communists and the serious detriment of British and American trade. So far Chiang and his lieutenants who rule Formosa can claim to be there as adherents of the Nationalist Government in Canton, and in accordance with the original agreement for a Chinese occupation of Formosa in advance of a Japanese peace treaty. But the Chiang regime in Formosa largely independent of any external authority, and if the Communists were to capture Canton, thus bringing about the collapse in law and precarious in fact. The island, which was developed economically by the Japanese has a flourishing export trade, but it probably cannot sustain for long, at least soldiers which has now been piled upon it. There is no immediate prospect of the Communists being able to launch a serious overseas invasion of Formosa, but if the Nationalist command ceased to be able to pay and feed its troops (whose homes are on the mainland), mutiny would certainly not be long in breaking out. The situation is further complicated by the tensions which have existed between the Formosans and the intruders from the mainland since the capitulation of Japan. The Formosans rose in revolt in 1947, but were suppressed with great severity. This was not a Communist but a provincial autonomist insurrection, and a strong desire for at any rate temporary independence is reported to exist among the Formosans. They were always an unruly element in the Chinese state and after fifty years of separation from China under an oppressive, but efficient, alien administration, they have no desire to be exploited by "liberators" from the continent, whether Kuomintang or Communist.

Nobody so far has paid any attention to the wishes of Formosa's inhabitants, but it is arguable that should be considered. The agreements made with the Nationalist Government about the provisional postwar occupation of Formosa would lapse if recognition were at any time to be withdrawn from it, unless these agreements were specifically to be renewed in favour of a Communist China; meanwhile, ultimate authority would revert to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers as part of his responsibility for all Japanese territory. The Americans, if they wished to do so, could provide sufficient protection for a Uno Commission to hold a plebiscite of Formosans on their future. But there is so far no indication that Washington now contemplates any Far Eastern policy involving new activity. If there are any misgivings about Formosa, however, they may emerge in the expected State Department White Paper on the Far East.

這篇文章是緊接在蔣介石訪問菲律賓的分析之後。蔣氏當時已非中華民國總統,但仍然有中國國民黨總裁的身份。他在7月10日從台北出發並抵達菲律賓,之後與菲律賓總統埃爾皮迪奧·季里諾(Elpidio Quirino)在碧瑤相談。按照抵達菲律賓時所發表的聲明,蔣介石是以「私人資格」受季里諾邀請前往中央社電(1949-07-11)〈總裁在菲發表聲明〉,《台灣民聲日報》。。

到了隔週7月23日,《經濟學人》在「海外世界」(The World Overseas)一欄又發表了一篇較長的分析,題目是〈在福爾摩沙的中國人〉(The Chinese in Formosa):

在福爾摩沙的中國人

當處置日本殖民帝國的計劃在太平洋戰爭期間制定的時後,沒人預料到將福爾摩沙島返還中國的計劃會有任何問題。日本在1895年時就從中國手上兼併福爾摩沙,以做為前一年中日戰爭勝利的戰利品;在絕大多數人口是說漢語,以及族裔上的背景,和先前領有的基礎下,中國對於領土返還的主張似乎不具爭議。因此,當日本在1945年投降時,中國不但被同意應該承擔對福爾摩沙的軍事佔領,且早在日本正式移交之前,就被指出已將其納為中華民國下的一個省份——這在和平條約訂定之前無法生效。美國以船運與運輸機將中國部隊送往福爾摩沙,並協助將日本人解除武裝與遣返,日本人在投降當時仍然在島上備有相當戰力。

福爾摩沙人並未表現出從日本的枷鎖中解放自身的跡象;沒什麼現存的東西足以稱之為反抗運動。不過的確對日本的統治是有相當的不滿,而且也和中國的中國人之間在一定意義上團結一致。在熱烈宣傳的各種承諾的預告之下,盟軍解放者一開始是受歡迎的。

然而,新時代的第一天卻帶來幻滅。如同一位福爾摩沙人責備美國軍官時所述:「你們只對日本投下原子彈;你們卻對我們投下中國軍隊。」陳儀將軍,即福爾摩沙解放後受派的首任長官,與其官員們,將福爾摩沙視為豐厚的戰利品,用以補償這支幸運的軍團在戰爭時期的所有損失與辛勞。福爾摩沙人被預期要對能夠從日本統治下解放,並重回中國民族的懷抱中而多加感恩,進而該預備將所有物資給予來自大陸的戰士英雄們的部署上。他們遭遇到一場強取豪奪的荒宴,而且還結合著無能與失序的管理,這些對他們來說就連在日本帝國主義苛政下的壞日子裡都未曾想像過。他們天真以為自己做為福爾摩沙人民,現在理應能夠從那些曾經使福爾摩沙成為日本許多利益來源的各種國有與私有事業中得到好處。但是每項利潤豐厚的事業或是工作都被新來者搶光,同時由於經營不善與掠劫,使得土地與工廠的生產力下降。

在日本治下福爾摩沙人並未擁有政治結社的自由,但在日本人投降的當時已經有一個團體,他們警覺到了被中國併吞的前景,並希望能夠在美國行使的聯合國託管之下自治。陳儀蹂躪下的一年,使自治運動快速成長,並且在1947年時以公開暴動告終。反抗遭受非常嚴厲的鎮壓,且造成一批最為傑出的福爾摩沙人,因受牽連或遭懷疑支持暴動而處決。不過,這場反亂,至少使得福爾摩沙人的積怨得到了一些注意;事件的發生受到外界報導,而南京的中國政府也注意到在這個中國省份的管理失當無論如何已經太過分了。陳儀將軍被去職,並且離開其不義之財前往大陸。在這之後,最糟糕的濫政在福爾摩沙已經受到糾正,且經濟上也有一定程度的復甦。不過這個政權最根本的特質仍然沒有改變;這是一個由大陸中國人為大陸中國人而設的福爾摩沙人政府。自從今年春天,該島成為落敗的國民黨的避難所兼軍事基地,且硬通貨與財物也湧入福爾摩沙,成為一些在地商人與店主的收獲。不過國家的資源受制於維持蔣介石將軍的戰鬥部隊,而且也沒有資金可供非軍事性的經濟發展或社會服務。*

來自大陸的窮親戚

中國官方對其福爾摩沙政策的合理化,是在於日本治理的時期並未給予福爾摩沙人足夠的政治或管理經驗,以運轉自己省份的事務,進而要將中國公務員送往當地來取代日本人。福爾摩沙人對此的回應,則是指大陸中國人自己本身就缺乏足夠能力以從事業務的官員,且如果能夠像南韓一樣,有一個由美國佔領的過渡時期,福爾摩沙人很快地就能習得負責崗位所需的資歷。從根本上來說,福爾摩沙人不是親日,而是從日本殖民時期繼承了如鐵路、道路、飛行場、教育、公共衛生,有序的管理,以及事業經營等的福爾摩沙人,相較之下將大陸中國視為落後。福爾摩沙人不懂為何要讓來自大陸的窮親戚吃盡這些東西的好處,因而想將這些收刮客們打發回去原來的地方。他們對新主人所產生的情緒,與戰間時期南斯拉夫的克羅埃西亞人面對塞爾維亞人時的感受非常相似,即哈布斯堡的舊臣民這才發現讓貝爾格萊德統治會是怎麼一回事。過去四年來如此痛苦的經驗,以至於對所有中國大陸當權抱持高度懷疑與敵意的態度,可能會是福爾摩沙人民將來很長一段時間的特質。

* 中國的國民政府軍在此出現所產生的國際問題在上週的124頁有所討論。

The Chinese in Formosa

WHEN plans were made during the Pacific war for disposing of Japan's colonial empire, it was not expected that there would be any trouble over the return of the island of Formosa to China. Japan had annexed Formosa from China in 1895, as part of the spoils of victory in the Sino-Japanese war of the previous year; the population was almost entirely Chinese-speaking and on ethnic grounds, as well as on the basis of former posses[s]ion, China appeared to have an indisputable claim to the reversion of the territory. When, therefore, Japan surrendered in 1945, it was not only agreed that China should undertake the military occupation of Formosa, but China was regarded as having incorporated it as a province of the Chinese Republic even in advance of any formal cession by Japan—which could not be effected until the conclusion of a peace treaty. American shipping and transport aircraft ferried Chinese troops across to Formosa and helped to disarm and repatriate the Japanese, who were still holding the island in strength at the time of the surrender.

The Formosans had shown no sign of liberation themselves from the Japanese yoke; nothing worthy of the name of a resistance movement was in existence. But there had been plenty of discontent with Japanese rule and a certain sense of solidarity with the Chinese of China. The Allied liberators, heralded with glowing propaganda promises, were at first welcomed.

The first days of the new era, however, brought disillusionment. As a Formosan put it in reproach to an American officer: "You only dropped the atom bomb on the Japanese; you have dropped a Chinese army on us." General Chen Yi, appointed the first Governor of liberated Formosa, and his officers regarded Formosa as a rich spoil of war which was to compensate this fortunate company for all the losses and hardships of the war years. The Formosans were supposed to be so grateful for being freed from Japanese rule and restored to the bosom of the Chinese nation that they should be ready to place all their worldly goods at the disposal of the warrior heroes from the mainland. They were subjected to an orgy of plunder and extortion, combined with and incompetence and disorder of administration such as in the bad old days of Japanese imperialist tyranny they had never imagined. In their innocence they had supposed that they, themselves, as the people of Formosa, would now have the benefit of the various Japanese state and private concerns which had made Formosa a source of so much profit to Japan. But every lucrative business or job was snapped up by the newcomers, while at the same time the productivity of estates and industrial plants declined owing to mismanagement and looting.

The Formosans had had no freedom of political association under Japan, but at the time of the Japanese surrender there already existed a group which was alarmed at the prospect of being absorbed by China and hoped for autonomy under a United Nations trusteeship to be exercised by the United States. A year of General Chen Yi's depredations caused a rapid growth of the autonomist movement and in 1947 it culminated in open insurrection. The revolt was suppressed with great severity, and a number of the most prominent Formosans, implicated in it, or suspected of supporting it, were executed. The rising, however, at least gained some publicity for Formosan grievances; reports of what was happening reached the outside world, and the Chinese Government in Nanking became aware that, in this province of China at any rate, maladministration and gone too far. General Chen Yi was removed from his post and departed to the mainland with his ill-gotten wealth. Since then the worst abuses of Chinese rule in Formosa have been remedied, and there has been a degree of economic recovery. But the essential character of the regime has not changed; it is a government of Formosans by mainland Chinese for mainland Chinese. Since the spring of this year the island has become the refuge and military base of the defeated Kuomintang and there has been an influx of hard money and valuables into Formosa, to the enrichment of some local traders and shopkeepers; but the resources of the country are being strained for the upkeep of General Chiang Kai-shek's fighting forces, and there are no funds for non-military economic development or social services.*

Poor Relations from the Mainland

The official Chinese justification for Government policy towards Formosa has been that the period of Japanese rule gave the Formosans no political or administrative experience sufficient to enable them to run their own provincial affairs, and that officials from China had, therefore, to be sent to take over from the Japanese. The Formosan answer is that the mainland Chinese were themselves too short of competent officials to be able to do the job, and that if there had been an interim period of American occupation, as in South Korea, Formosans could quickly have acquired the qualifications for responsible posts. Fundamentally, the Formosans, without being pro-Japanese, look down on mainland China as backward by contrast with the endowment of railways, roads, airfields, education, public health, orderly administration and business management which Formosan has inherited from the Japanese colonial period. The Formosans do not see why the benefits of all these things should be eaten up by the poor relations from the mainland, and would like to pack off the swarming carpet-baggers back to the places whence they came. Their sentiments towards their new masters have a great similarity to those of the Croats towards the Serbs in Jugoslavia between the wars, after the former subjects of the Hapsburgs had discovered what it was like to be governed from Belgrade. So bitter has been the experience of the last four years that an attitude of deep suspicion and hostility towards all Chinese mainland authorities is likely to be characteristic of the Formosan population for a long time to come.

* The international problems created by the presence of Nationalist forces in China were discussed on p. 124 of last week's issue.

文章最後以克羅埃西亞人的處境類比當時的台灣人,克羅埃西亞是在1918年時脫離瓦解的奧匈帝國,加入「斯洛維尼亞人、克羅埃西亞人與塞爾維亞人國」,而這個國家不久後又與「塞爾維亞王國」結合成為「塞爾維亞人、克羅埃西亞人與斯洛維尼亞人王國」,即南斯拉夫的前身。